Note: this article references the seasons in the southern hemisphere. Our northern cousins need to reverse the seasons.

One of the questions I am asked most often is, “When do the seasons start?” Given that treatments are stronger when an Element is treated in its own season, it is important to know when each season begins. Here in Australia the spring is considered to begin on September 1st, summer on December 1st, autumn on March 1st and winter on June 1st. Some sources suggest this is a historical convention because the soldiers who guarded the convicts in the early years of European settlement changed from winter to summer uniforms on December 1st and from summer to winter uniforms on June 1st.

Meanwhile, in Europe and North America, the start of each season is based on the solstices and equinoxes, so spring begins on the spring equinox, March 21st, summer on the midsummer solstice, June 22nd, autumn on the autumn or fall equinox, September 23rd, and winter on the midwinter solstice, June 21st. (These dates can change by a day depending on which time zone you live in.)

Neither of these conventions describes the charting of the seasons in the Chinese medicine calendar whose method presupposes that the midwinter solstice marks the middle of winter, and the midsummer solstice marks the middle of summer. The clue is in the name!

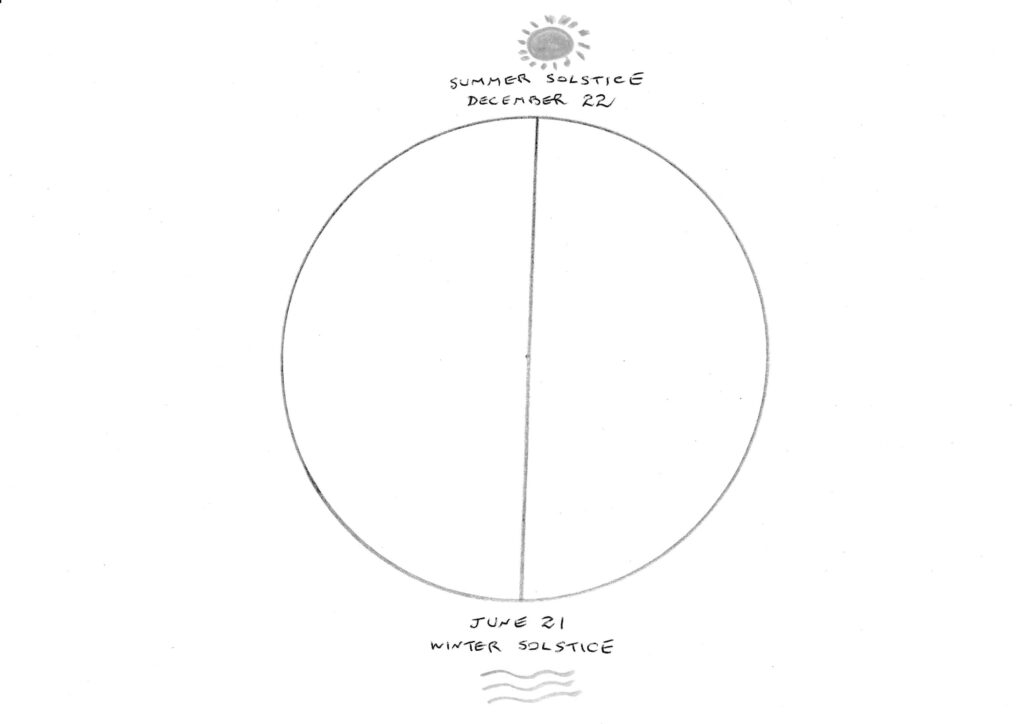

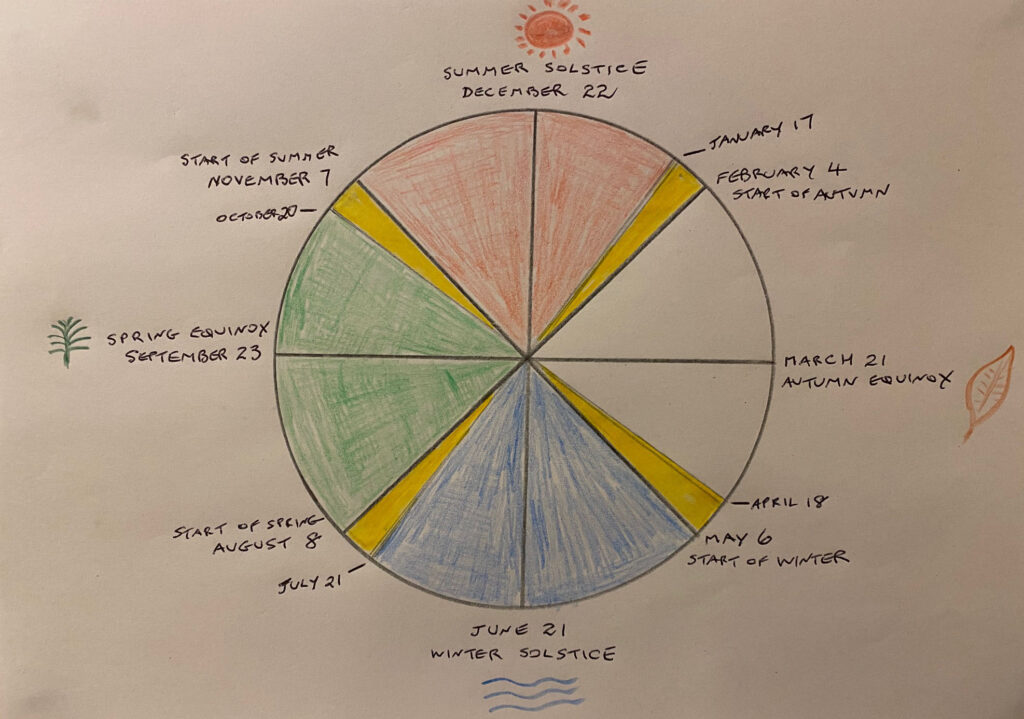

Let’s begin with this chart of the solstices where the midsummer solstice at the top represents the peak of summer, of the Fire Element and of the greatest yang. The midwinter solstice at the bottom represents the depth of winter, of the Water Element, and of the deepest yin.

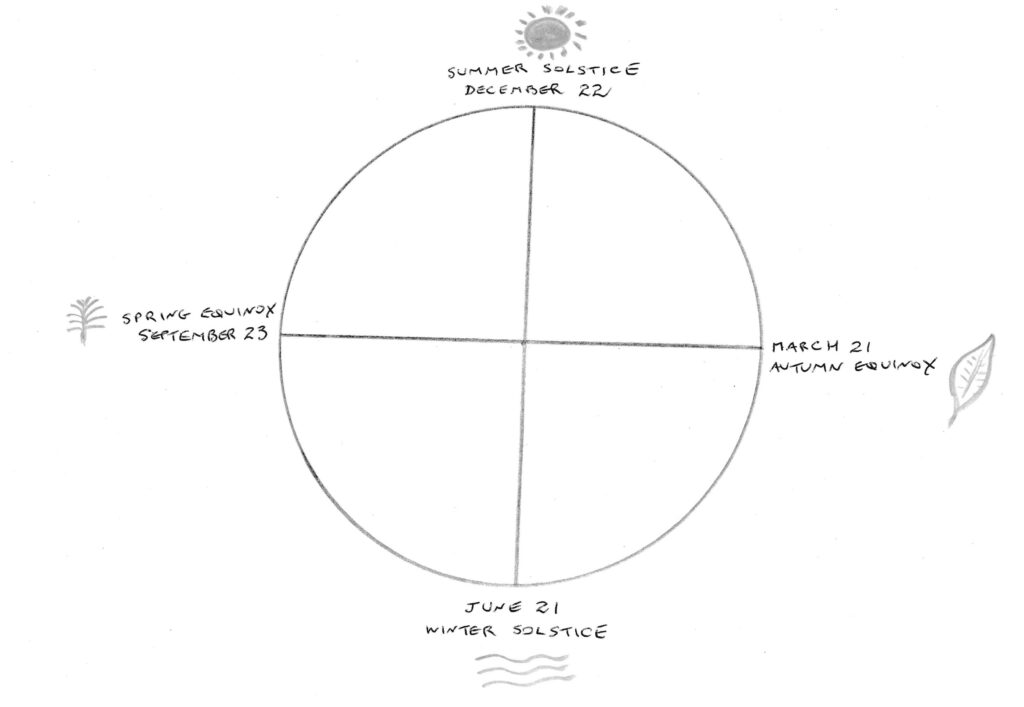

Now let’s add the midpoints between the solstices. These are the equinoxes. The word equinox means equal night; in other words, the days and nights are of equal length and the time of the sunrise in the morning matches the time of the sunset in the evening. While these may seem to be the same thing, energetically, things are rising at the spring equinox with the Wood Element (yang), while things are falling at the autumn equinox with the Metal Element (yin).

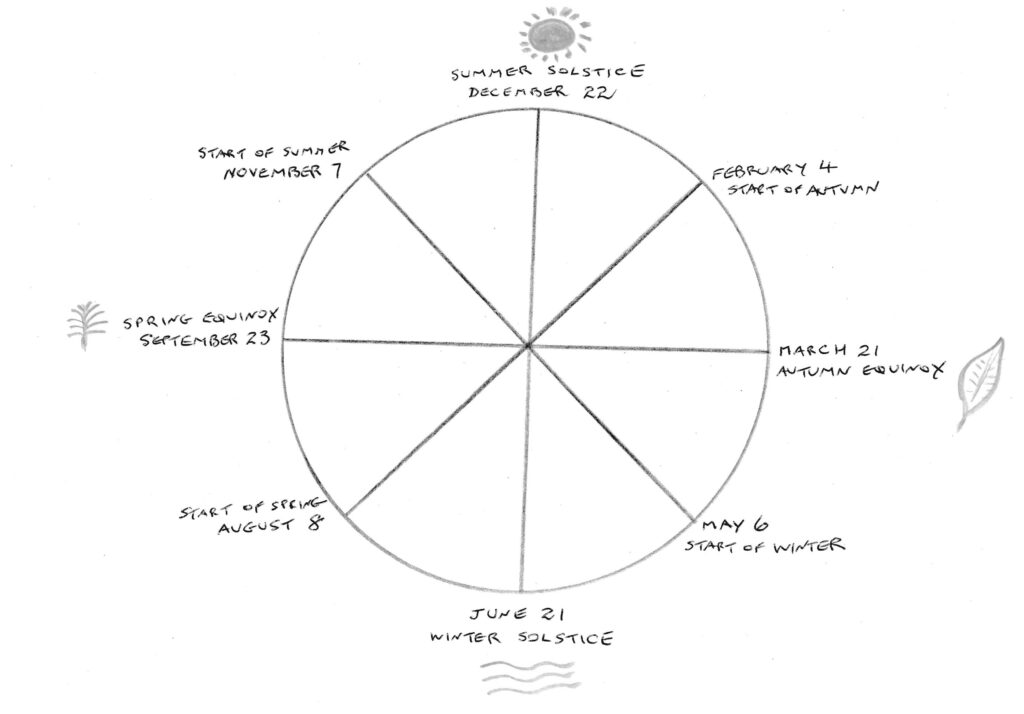

Next, we can divide these four “quarter days” to find the “cross-quarter days”. It is these dates which give us the start of the seasons in the Chinese medicine calendar. Thus, August 8th is the start of spring, November 7th the start of summer, February 4th the start of autumn, and May 6th the start of winter. If this seems far too early, consider that in the ancient Celtic tradition of northern Europe, the Celts also had an eye for these cross-quarter days, but they celebrated them even earlier. For them, Imbolc (lamb’s milk) started spring on February 2nd. The Christian church adopted this as Candlemas and now in North America it is Groundhog Day. The Celtic Beltane on May 1st marked the beginning of summer and the betrothal of young couples. Lammas on August 1st marked the start of autumn and the harvest time. Finally, Samhain on October 31st was the beginning of winter when livestock was brought in from distant pastures. Now of course, this is celebrated as Halloween.

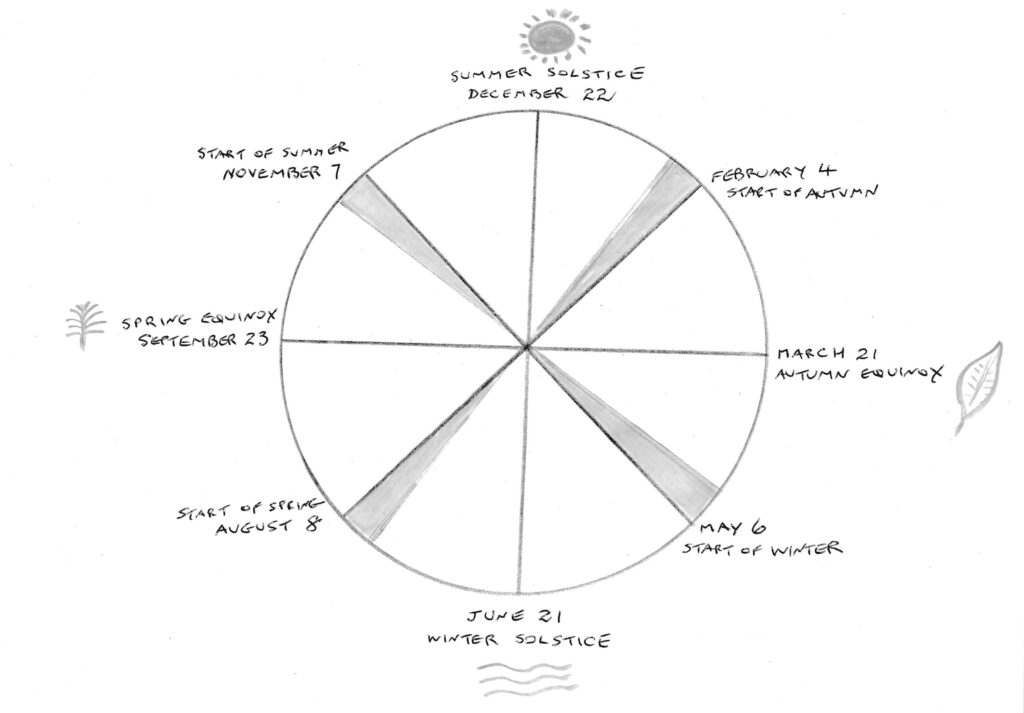

So now we have four distinct seasons representing four of the Five Elements: spring is Wood, summer is Fire, autumn is Metal, and winter is Water. But what of the fifth Element, the Earth? The classic text, Neijing Su Wen tells us that Earth corresponds to late summer. (Su Wen chapter 4) This is the harvest time, sandwiched between summer and autumn. But why is such an important Element only given a sandwich instead of a whole meal? Elsewhere the Su Wen tells us, “In the division of the four seasons, the time of the [Earth] is the last eighteen days of each season.” (Chapter 29) If we add up the 4 x 18 days we get 72 days altogether which gives the Earth its full quota. So instead of just being the late summer, it is also the late autumn, the late winter and the late spring.

These four blocks of 18 days are periods of transition, a time when one season is blending into the next. Transition, connection, mediation, these are all good words to describe the qualities of Earth and its central role of connecting the four seasons together.

Finally, then, we can calculate the dates of the beginnings of these four transitions by counting back 18 days from the cross-quarter days. The late spring begins on October 20th, late summer on January 17th, late autumn on April 18th, and late winter on July 21st. This latter date has just passed and provided the impulse for this blog.

Clinical applications

Going back to the classic, Su Wen chapter 22 advises that spring is the best time to treat conditions of Liver and Gall Bladder, summer is the best time to treat Heart and Small Intestine, late summer is the best time to treat Spleen and Stomach, autumn is the best time to treat Lung and Large Intestine, and winter is the best time to treat Kidney and Bladder. The cosmological Qi is at its strongest in the organs that correspond to the season and so treatment gets an extra boost. Moreover, it is my experience that the boost is stronger in the first half of the season; past the half-way point of the season, this power begins to wane.

If we take this information in conjunction with Su Wen 29, we can infer that treating the Earth organs of Spleen and Stomach will also have more power in those other periods of 18 days when Earth is mediating the transition between seasons. As it is now.

A simple way to support the Earth at these times is to hold the Earth points on these Earth meridians. They are Stomach 36 and Spleen 3. If you need a reminder of their location, just click on the links. I wish you well in this time of transition.